Googling ‘what is bad naked' takes a particular type of courage. Thinking about what I might look like cutting my toenails, sitting naked on the toilet, is another type. It turns out that Jerry Seinfeld and Kayla Witt have been thinking about this for some time.

A series of paintings currently in production in Kayla Witt's studio directly relates to the 165th episode of Seinfeld, The Apology. Witt explains, "In the episode, Seinfeld has a new girlfriend who is naked around the apartment all the time. He complains that there's a difference between good naked and bad naked; that he doesn't want to see her opening a pickle jar or wet sanding the floor naked." Of course, what Jerry gripes about is female nudity in a non-sexual context – hardly a new complaint. Inviting friends to think about their bad naked, Witt photographed them at their homes and presents to us images that Seinfeld might rather not see.

In one of Witt’s paintings, Classically So Bored of Sweating, Pascale, the subject, hand-sands her back deck with one leg wrapped around a patio chair for comfort. The exterior glass door with built-in Venetian blinds, and the red and plum brick façade from the 1950s places you on a second-floor balcony outside an unmistakable southern Ontario home. Perhaps my favourite, if not for the title alone, I Want to Smell Like a Thriving Stock Market, depicts a young woman painted in a vibrating yellow, as she lays on the kitchen floor, fixing the exposed pipes under the sink. The bold and graphic kitchen of blues, yellows, purples and oranges feels familiar. Her body against the striking red-checkered floor sends a shiver up my cold-prone spine.

Classically So Bored of Sweating, oil on canvas, 40 x 40 inches, 2018

In Gloria Steinem's seminal essay, In Praise of Women's Bodies she writes, "But for women especially, bras, panties, bathing suits, and other stereotypical gear are visual reminders of a commercial, idealized feminine image that our real and diverse female bodies can't possibly fit. Without those visual references, however, each individual woman's body can be accepted on its own terms. We stop being comparatives. We begin to be unique" (Steinem). I'm not sure what George Constanza would think about that, but he would likely pick a true to character line such as, "The sea was angry that day, my friends, like an old man trying to send back soup in a deli..." (Seinfeld). Famously Seinfeld is a show about nothing, but Steinem certainly isn't. Witt too. She's not about nothing either.

I Want To Smell Like A Thriving Stock Market, oil on canvas, 50 x 50 inches, 2018

The women in these paintings are not unattractive and indeed maintain, to some degree, the gender and body-type expectations we're accustomed to seeing. Pushing against the Jerry Seinfelds, I wonder if Witt has considered painting differently-abled bodies in her work. This is something that I try (sometimes failing – remarkably failing) to be cognitive of, because if we're not challenging representational norms with inclusivity now, then when will we? "Ableism is defined in disability studies as discrimination in favour of able-bodied people. The ableist views able bodies as the norm in society, implying that people who have disabled bodies must strive to become that norm" (Watson). Bringing these ideas into popular culture Bueva is thinking similarly about the embodiment of women's sexuality, "Blatant sexualization of the media along with commodification and normalization of erotic imagery in public discourse further problematize issues of disabled visibility, implicitly resulting in female disabled bodies' symbolic oscillation between exclusion and "enfreakment". Traditionally viewed as not ideal reproducers or embodiment of desirable or even acceptable femininity, women with disabilities' sexuality is either marginalized and excluded as unacceptable and deviant or fetishized and incorporated into the booming and rapidly expanding representational idiom of pornography" (Bueva 9).

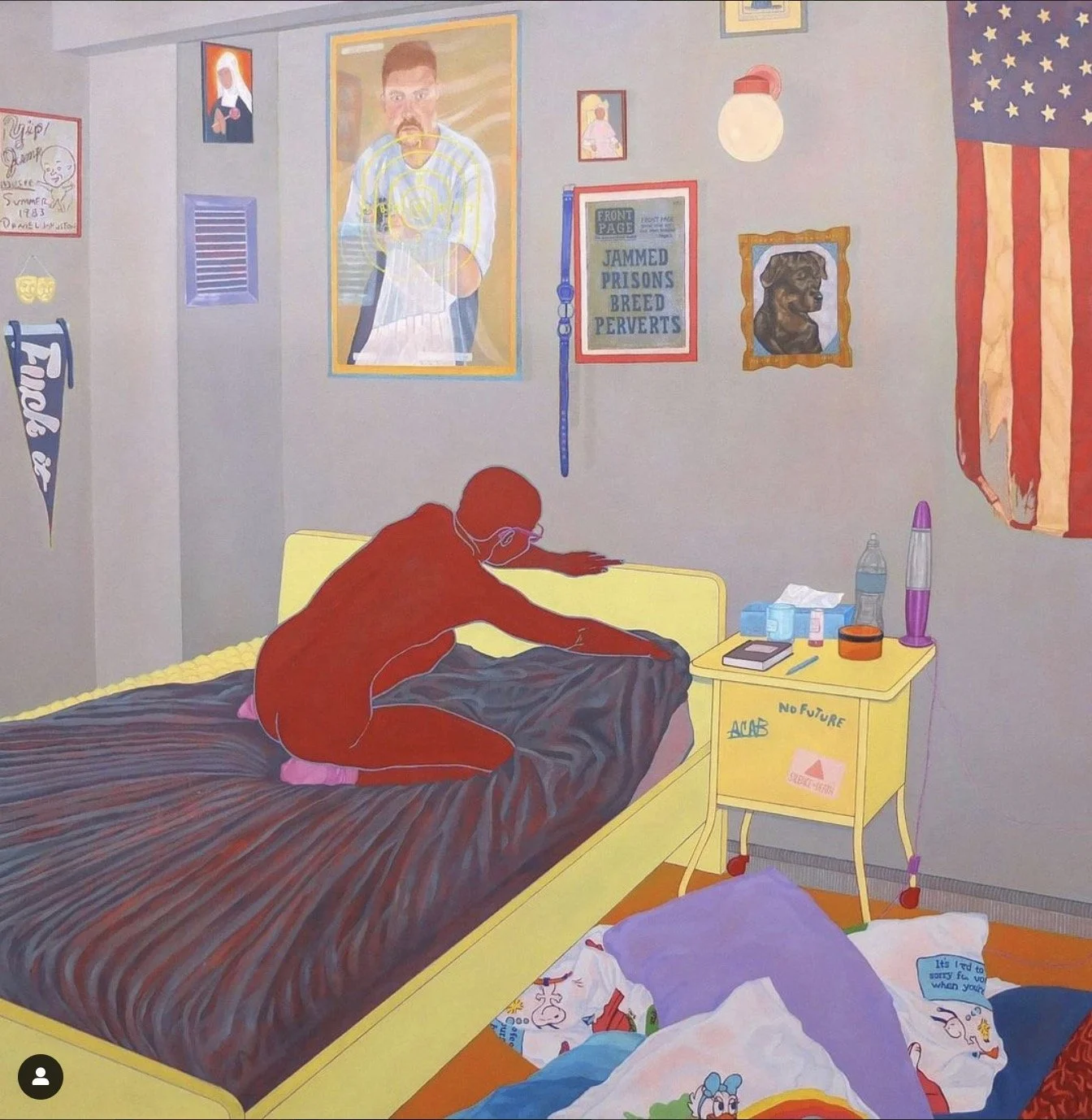

While the body is prominent and was the starting point for this series, Witt tells me that she has increasingly been thinking about architecture and interiors. Contemplating how different spaces function and how they do so across gender, race and class, she seems more critical of the spaces we find ourselves. I Only Decorate with Satire is a work-in-progress, of Alana in her bedroom, naked of course, tugging to pull the top right corner of the fitted sheet over the mattress. This painting, unlike the earlier ones, has muted grays, blues and reds and in contrast to the others, there reads a heaviness to it. Immediately the colours help to convey something unnerving – it's America-praising in a hate propaganda way. The dirty and mangled American flag that flanks the wall, and the framed newspaper headline that reads, "JAMMED PRISONS BREED PERVERTS", doesn't taste of irony. This friend seems to fulfil Witt's inquiry into how the materials we keep in our spaces can either reveal or betray our own beliefs, and how the objects she paints with a person provides them with a new agency. I believe her when she tells me her Calgary-based high school classmate, who works in prison reform, is not who the objects imply she is. This still doesn't sit right with me and as the viewer, I appreciate being pushed.

I Only Decorate with Satire, oil on canvas, 2019

Aside from I Only Decorate with Satire, the interiors in this series of paintings make me wonder if LA's sunny weather, where Witt lives part-time, influences her pallet. David Hockney moved from Britain to La-La Land in the 1960s, and there's a technical and an aesthetic kinship between Witt's work and his pool paintings of the same era. There is also an affinity to his more recent work, The Brass Tacks Triptych, 2017 with a focus on interior spaces. Even if one can't forgive Hockney for his abundance of mono-characters, there is a quiet beauty in his The Group, 2014 paintings, which echoes with those of the artist.

At the end of my visit, Witt says with an almost unexpected revelation, that perhaps all of her work is about nothing. Steinem went undercover as a Playboy Bunny in 1963, which could also be nothing; Witt's paintings feel a bit like that.

Kayla Witt in her studio, 2019. Photo by b wijshijer